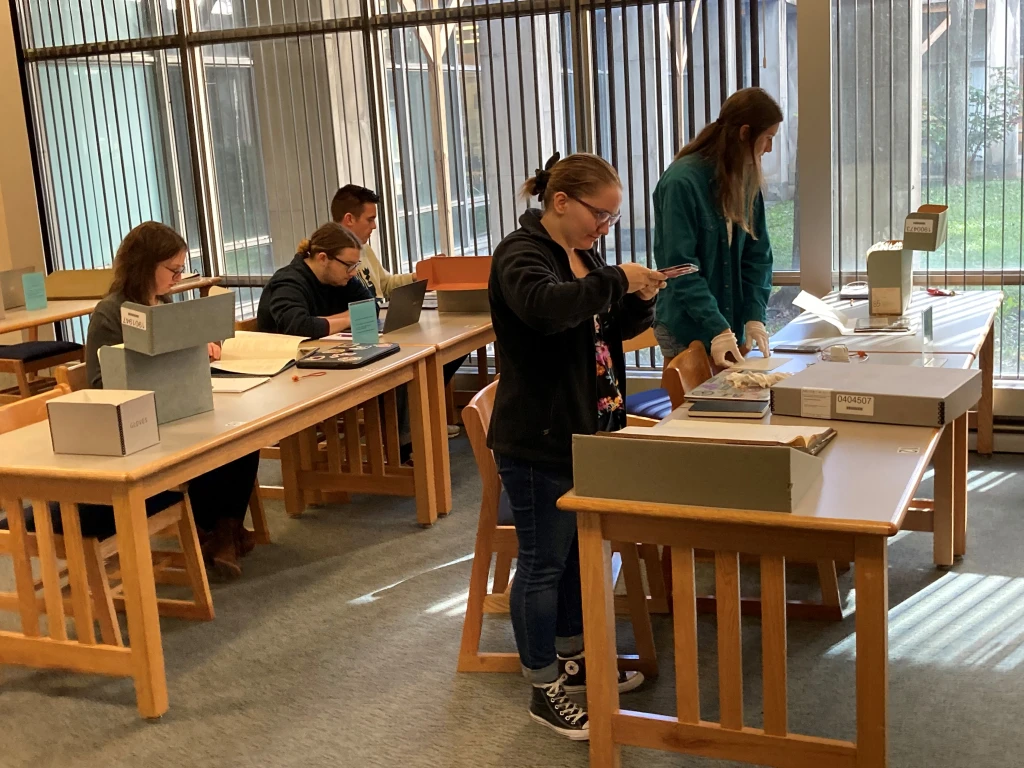

This fall I’m fortunate to be teaching again a course called Digital History. I first developed the class in 2014 and offer it on an every other year cycle. Unlike my staple classes in the ancient world, I created this course primarily to train history and public history majors at Messiah University how to use technologies for historical studies and how to think critically about information, its production, and dissemination. We spend much of our time tinkering with tools like Zotero, Omeka, WordPress, Microsoft Excel, and Story Maps, but we also devote a couple of afternoons viewing and digitizing manuscript group boxes at Pennsylvania State Archives and Dauphin County Historical Society archives to create projects for the public. I’ve tended to teach the course by centering around projects related to the historical study of Harrisburg, the capital city of Pennsylvania, especially broad historical problems, such as Harrisburg’s successful City Beautiful Movement and the state’s destruction of the Old Eighth Ward, the multi-ethnic community near the capitol. Over nearly a decade of running this class, our students have learned new technologies, produced a range of projects, and written dozens of blog posts. And I myself have learned some new technologies along the way.

This time around I’ve assigned as my core text Adam Crymble’s Technology and the Historian: Transformations in the Digital Age (University of Illinois Press: 2021), a book that differs, from others I’ve used in the past, in its focus on placing historians’ use of technology into a historical framework. The work offers not so much the latest discussion of a group of historians about the relationship of technology to historical work, or a guide to developing history for the web, but a critical history of how historians have actually used technology in the computing age. What I’ve enjoyed about this text is that it constantly contextualizes the historian’s embrace of technology, sets it into a long time frame (stretching back well before computers were invented), and brings time-perspectivism to the study of digital history and its facets. Crymble gives me a greater appreciation for how my own course in “digital history” fits within and reflects broader patterns of discourse about technology and the past.

One of the final chapters of Technology and the Historian got me thinking about the history and purpose of this website. Titled the “rise and fall of the scholarly blog,” Crymble traces the origins of blogging in history (out of zine publishing, newsletters, and listserve discussion groups), and describes how the blog, for a brief moment, gave historians a sense of shared identity on the web, creating an imagined community and making “historical studies a more self-reflective space.” If at first, students of history adopted blogging twenty years ago to rant in virtual community, eventually historians (by 2006-2008) took up Dan Cohen’s call to professors to “start your blog” and use it as a means of disseminating work as professionals. Crymble quotes (p. 159) Tim Hitchcock’s observation in 2014 that blogging forms “a way of thinking in public and revising one’s work, to make it better, in public.”

In his interest in the history of historian and technology, Crymble understandably writes about blogging in the past tense because newer, quicker forms of social communication like Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram have since eclipsed the blog and killed its momentum as a form of social discourse. Yet, the blog lives on, of course, in the historian’s (and archaeologist’s) toolkit precisely because it occupies a kind of short-form public scholarship that is distinct from other types of social media. I respect those friends and colleagues like Bill Caraher (over at Archaeology of the Mediterranean World) and John Fea (now at Current) who have written consistently — daily even — for fifteen years or more both to think and revise their professional work in public and to reflect on the latest. As I tell my students in digital history, short-form essays remain an important role in generating knowledge about historical subjects for wider audiences. Even when engines of websites fail, as they all do eventually, their content becomes part of the web’s trove that the search engine finds, archives, and creates access to.

I’ve thought about it and am not quite ready to end the blog component of Corinthian Matters, a site with its own starts and stops that reflects the rhythms and priorities of my personal and professional life. This year, as I return to something of a more normal academic cycle, I hope to give a little more regular attention to the site, especially as I work on a series of Corinthian-related teaching and research topics.

Leave a comment